In the seventh month, on the twenty-first day of the month, the word of the Lord came by the hand of Haggai the prophet, “Speak now to Zerubbabel the son of Shealtiel, governor of Judah, and to Joshua the son of Jehozadak, the high priest, and to all the remnant of the people, and say, ‘Who is left among you who saw this house in its former glory? How do you see it now? Is it not as nothing in your eyes? Yet now be strong, O Zerubbabel, declares the Lord. Be strong, O Joshua, son of Jehozadak, the high priest. Be strong, all you people of the land, declares the Lord. Work, for I am with you, declares the Lord of hosts, according to the covenant that I made with you when you came out of Egypt. My Spirit remains in your midst. Fear not. For thus says the Lord of hosts: Yet once more, in a little while, I will shake the heavens and the earth and the sea and the dry land. And I will shake all nations, so that the treasures of all nations shall come in, and I will fill this house with glory, says the Lord of hosts. The silver is mine, and the gold is mine, declares the Lord of hosts. The latter glory of this house shall be greater than the former, says the Lord of hosts. And in this place I will give peace, declares the Lord of hosts.’”

Zerubbabel is from the line of David, though he is only a governor in the empire now.

That and many other things don’t seem as grand as David and Solomon. In fact, even the construction project on the Temple suffers in comparison even to the last state of Solomon’s Temple before the exile. Thus, from Ezra 3 (which is background to the prophecy of Haggai above):

And all the people shouted with a great shout when they praised the Lord, because the foundation of the house of the Lord was laid. But many of the priests and Levites and heads of fathers’ houses, old men who had seen the first house, wept with a loud voice when they saw the foundation of this house being laid, though many shouted aloud for joy, so that the people could not distinguish the sound of the joyful shout from the sound of the people’s weeping, for the people shouted with a great shout, and the sound was heard far away.

(Note, “Lord” is often YHWH and should be in all caps. I’m too lazy to hunt and change it.)

So no independent kingdom and no grand Temple. Solomon’s Temple had been far grander than the Tabernacle, just as the Davidic Covenant was grander than the Mosaic economy we read about in Judges. And there had been promises made that the New Covenant would be even grander. As we read in Jeremiah 16:

Therefore, behold, the days are coming, declares the Lord, when it shall no longer be said, ‘As the Lord lives who brought up the people of Israel out of the land of Egypt,’ but ‘As the Lord lives who brought up the people of Israel out of the north country and out of all the countries where he had driven them.’ For I will bring them back to their own land that I gave to their fathers.

But what happened during the first Exodus? God made a covenant with Israel on Mount Sinai, gave them the Law, and had them build a house for him to dwell in their midst.

So also Jeremiah, having promised a new and greater Exodus, must promise a new and greater covenant:

Behold, the days are coming, declares the Lord, when I will make a new covenant with the house of Israel and the house of Judah, not like the covenant that I made with their fathers on the day when I took them by the hand to bring them out of the land of Egypt, my covenant that they broke, though I was their husband, declares the Lord. For this is the covenant that I will make with the house of Israel after those days, declares the Lord: I will put my law within them, and I will write it on their hearts. And I will be their God, and they shall be my people. And no longer shall each one teach his neighbor and each his brother, saying, ‘Know the Lord,’ for they shall all know me, from the least of them to the greatest, declares the Lord. For I will forgive their iniquity, and I will remember their sin no more.

So what is God saying through Haggai? (“Work, for I am with you, declares the Lord of hosts, according to the covenant that I made with you when you came out of Egypt. My Spirit remains in your midst. Fear not.”). Despite the fact that “this house” is incomplete.. Despite the fact that it will never be as grand as Solomon’… Nevertheless, it is greater and the covenant is greater. God is dwelling in their midst just like in the Tabernacle and in Solomon’s Temple.

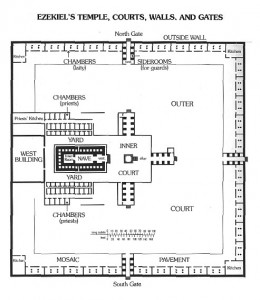

If you read the description of Ezekiel’s visionary Temple, you will see something that surpasses the the capabilities of human architecture. The Tabernacle pictured the Mosaic Covenant and the Temple pictured the Kingdom Covenant but the Imperial Covenant surpasses the possibility of architectural representation.

But what about the prophecy? (“Yet once more, in a little while, I will shake the heavens and the earth and the sea and the dry land. And I will shake all nations, so that the treasures of all nations shall come in, and I will fill this house with glory, says the Lord of hosts.”)

Read the book of Esther. It ends with an international worldwide Holy War in which the people refuse to take the plunder when they are given victory. (God had declared Holy War on the Amalekites and Saul the Benjaminite lost his throne because he didn’t kill their king Agag. Esther is about a Benjaminite confronted by an Agagite.) So where does this plunder go?

It would seem obvious to me that it goes to the Temple, just like the Israelites were earlier restricted from taking the plunder of Holy War and gave it to the Tabernacle.

So Esther isn’t just some story, but fulfills the pattern and the prophecies of the earlier “New Covenant.”